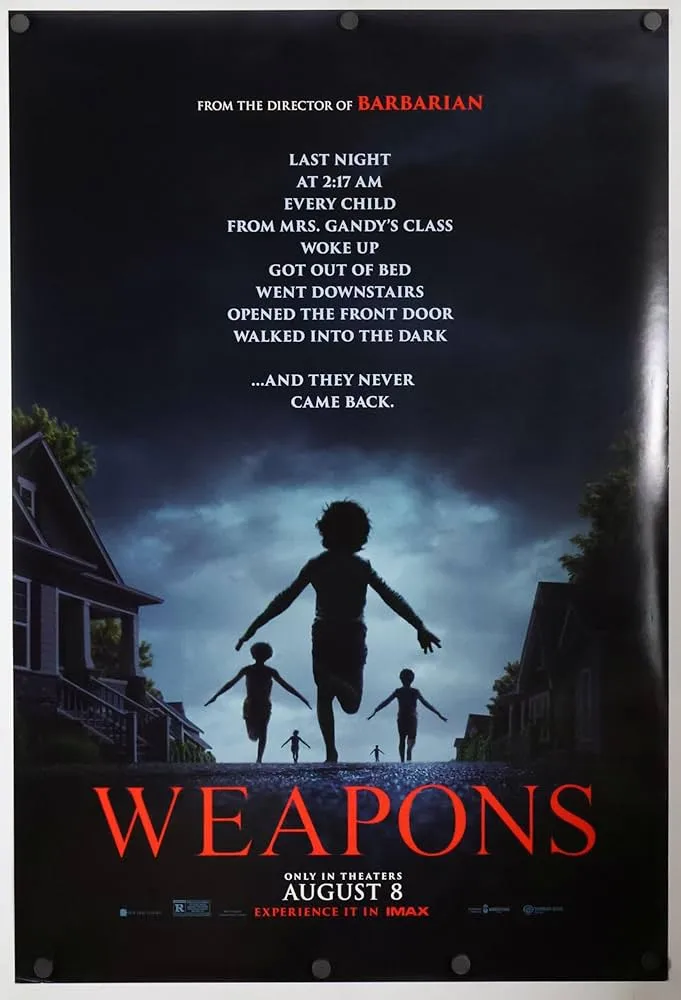

Scream!

Given the release of the sixth installment of the scream franchise, it’s only fitting to go back to the original and see just what exactly makes it such a classic.

Scream (dir. Wes Craven) was released in 1996 following a surge in the slasher genre in the late 1970s to 80s. Movies like Halloween, Nightmare on Elm Street, and Friday the 13th all became staples of the genre. Eventually, the appeal of the genre lessened, with people growing tired of the tropes found in each movie. A masked killer terrorizing a small town, attacking people until he’s made his way to the final girl, who ends the movie having barely survived and heavily traumatized. The reason Scream sets itself apart from other slashers of its time is how it acknowledges, plays into, and then inverts those tropes to make a classic horror-satire-comedy mashup that’s still renowned today.

Scream is a self-aware horror movie. During her first call with Ghostface, protagonist Sidney Prescott remarks how unrealistic horror movies are, complaining about how they all have a “girl who can’t act who is always running up the stairs when she should be running out the front door.” Immediately following this interaction though, she finds herself face-to-face with Ghostface and her first instinct? To run up the stairs instead of the front door. This is a nod to common tropes from Craven, being one of the first in the slasher genre to openly acknowledge and poke fun of common horror tropes. Scream’s self-awareness also comes in the character Randy Meeks. Randy’s a horror fanatic who acknowledges just how movie-like the situation is, preaching to a house party the “rules” to survive a horror movie, all of which have been broken by that point in the movie. The movie’s end defies tropes as well. The final interaction between Sidney and Billy Loomis, who is revealed to be one of two Ghostfaces present in the film defies horror norms. In several slashers there’s always a moment in the final scenes of the film where the assumed-dead villain comes back miraculously for one final battle. When this trope is mentioned by Randy and Billy jolts awake, Sidney ends it. “Not in my movie,” she says, ending Billy for good.

Billy acts as an additional inversion of slasher tropes. He is the rugged, seemingly perfect boyfriend to the protagonist who swoops in and saves her whenever there’s a threat to her life, but he is also the threat to her life. Billy is suspicious from the start, talking about the killings in a shockingly cavalier way and appearing right outside Sidney’s window seconds after the attack, but the audience is kept guessing as he keeps his guard up until the 3rd act of the movie, where he and Stu Macher reveal themselves to be the murderers plaguing Woodsboro. Billy’s role as both The Perfect Boyfriend and The Masked Killer subverts people’s expectations made from all the slashers released before Scream.

Scream is a horror, a slasher, and comedy all wrapped into one easy-to-digest and enjoyable film, and arguably one of Wes Craven’s best works. And the reason it works is because it goes against everything horror was at the time. It was predictable when it wanted to be, and unpredictable when it needed to be.

Julian Payne is a senior at Richwoods. He’s been in Newspaper and Interact the last two years. He enjoys literature, film, and music. He hopes to write...