“There are many career opportunities in the healthcare industry”: An Interview with Dr. Timir Baman

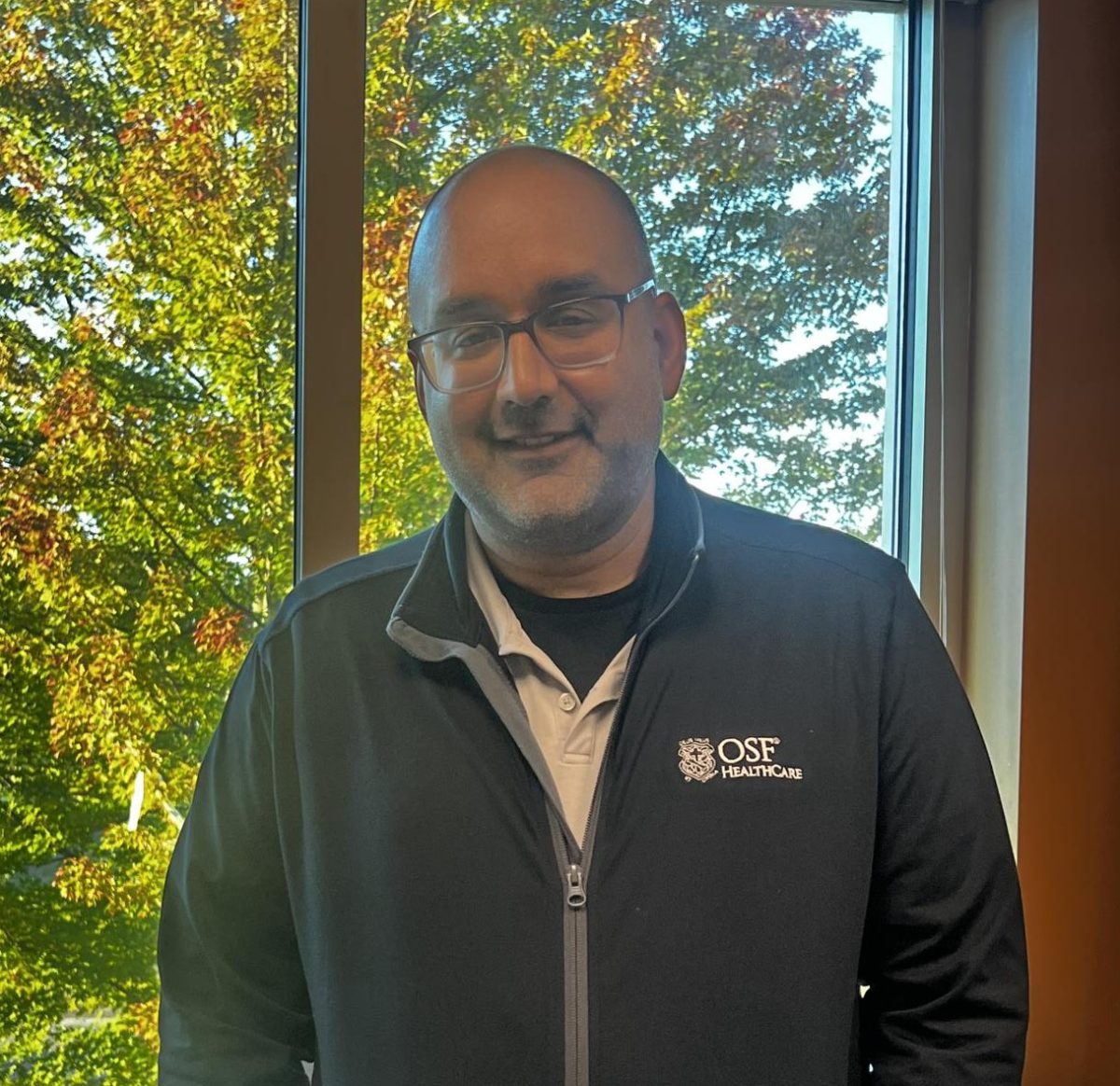

At 6:30 p.m. I hop out of the car and make my way to the back door of the brick building of the OSF Cardiovascular Institute on Knoxville Avenue. Stopping in front of the metal doorway, I text my interviewee, Dr. Timir Baman, a Richwoods alumnus of class of 1984 and cardiologist/electrophysiologist at OSF Saint Francis Medical Center. Looking into the sky, I observe that it is already twilight, and the sun is about to set. Since my interview appointment is scheduled after the regular hours of the clinic, I have been instructed to come to the side door. A few minutes later, the door opens, and Dr. Timir Baman himself lets me in. He is wearing square-shaped glasses and a collared shirt and a navy jacket with the words OSF Healthcare embroidered on it. After our brief greeting, we walk three flights of stairs up to an office space full of cubicles and conferences rooms. Glancing around, I notice that a few staff are still working in their cubicles. We quietly head to a spacious conference room with tall windows covering one of the walls. There, I sit down and promptly start the interview.

Dr. Baman grew up in Brimfield, Illinois and later moved to Peoria during 8th grade. When asked about his experience at Richwoods, Dr. Baman recalls that he had a good time. He specifically remembers playing football at Richwoods for three years. “It was a lot of fun…I wasn’t good at it, but I enjoyed it,” Dr. Baman says. As for classes, he enjoyed the physics class, which was taught by Mr. Bruce Garrison. During his time, physics and chemistry were the only two AP classes available at Richwoods. The IB program was not yet available to students either. “Everything was regular honors and regular classes,” Dr. Baman recalls. Throughout high school, Dr. Baman took both APs. Although he enjoyed AP physics, AP chemistry was one of his most challenging classes. Ultimately, Dr. Baman found that chemistry was not for him and decided to drop the class in his senior year.

Another memorable moment of his time at Richwoods was when he did his volunteer service at South Side Mission. “I got a bunch of people in the class every now and then especially around Thanksgiving time. We would go spend time and help people out …During the holidays I think people always need some help.” This experience may have spurred Dr. Baman’s passion for service, which has led him to his medical career.

When asked about the student life back then, Dr. Baman says, “I think things were easier back then, there were no phones, no social media, the school was collegial, and we all worked together and had a good time.” Dr. Baman recollects that if a student brought a phone to school, teachers would take it away. Students were also not allowed to bring water bottles to class. They would wait until the passing period to take a sip of water at the fountain. “Life was very simple back then,” he reminisces.

Dr. Baman enjoyed his time with friends and classmates the most at Richwoods. He describes how school life was very different back then. “You would go outside and come back home when the lights go down, that was the daily thing.” However, as time went on to senior year, Dr. Baman started to become more focused on his schoolwork. As he started to figure out the direction of his life, he was accepted into the University of Chicago.

Looking back at his college years, Dr. Baman recollects that it was a good but also a hard time for him. Dr. Baman was a biopsychology major, a field that prepares students for careers in the medical field. In college, Dr. Baman quickly found that it was easy to fall behind in class. “Nobody tells you what to do. The people who do well in college are not the smartest, they are the people who manage their time the best, the ones who were organized and didn’t fall behind.”

After college, Dr. Baman entered the medical school at Pennsylvania State University. “It was challenging to get in. For some people, it may not be, but for me, it was very challenging to get in.” When asked why he found the admission to a medical school was so difficult, Dr. Baman replies, “If you’re trying to go to a medical school, grades are very important, there is a test called the MCAT, which is difficult. There’re a lot of things that they research and a lot of things they look for. For those entering the medical field, it is a long road.”

After two years in Penn State’s medical education program, Dr. Baman started doing rotations through different wards such as pediatrics, surgery, oncology, etc. He quickly narrowed his interests down to cardiology. “When someone comes in with a heart attack, you can fix it. Things are fixable and the technology used in cardiology is very good and is always changing.” After four years of medical school, a three-year residency in internal medicine, and a three-year fellowship in cardiology, Dr. Baman spent two more years receiving his training in electrophysiology, which focuses on the heart’s electrical system.

After his training, Dr. Baman began his career in Peoria at OSF Saint Francis Medical Center. In 2009, he collaborated with the University of Michigan Frankel Cardiovascular Center and cofounded a program called “Project My Heart Your Heart (MHYH),” which allows patients with abnormal heart rhythms to have access to reused pacemakers (medical devices that are put in the heart to stabilize abnormal heart rhythms). The program collects pacemakers from people who have passed away. The pacemakers are then sterilized and shipped to countries where medical devices like pacemakers are not affordable. From there, the pacemakers are implanted in patients whose quality of life suffers due to malfunctions in the heart’s beating process. For example, a patient may have a heart rate of 30-40 beats per minute while a normal heart rate is 60-100 beats per minute. “There are people who send letters and pictures. We have also met a few patients that have the pacemakers put in and they are very grateful,” Dr. Baman says.

Looking back on his experiences, Dr. Baman’s piece of advice for any high school students who are looking for a potential career is to look into the healthcare industry. He says that a career in healthcare is flexible and can be tailored to individuals. If an individual does not want to do much schooling, it is fine. Dr. Baman suggests that students look into becoming a technician or a nurse, whether it be a nurse in an operating room, an ultrasound technician, or a radiology technician. “Being a nurse is great job, and I think people often times have misconceptions of what the nurse does. There’re so many different kinds of nurses. You can have a nurse on a regular floor which takes care of you. You can be in the OR where you can assist a surgeon.” All jobs in healthcare have good salaries and are in high demand due to a shortage of workers in the medical field. “A hospital job has always got something for every single type of person in my opinion,” he says.

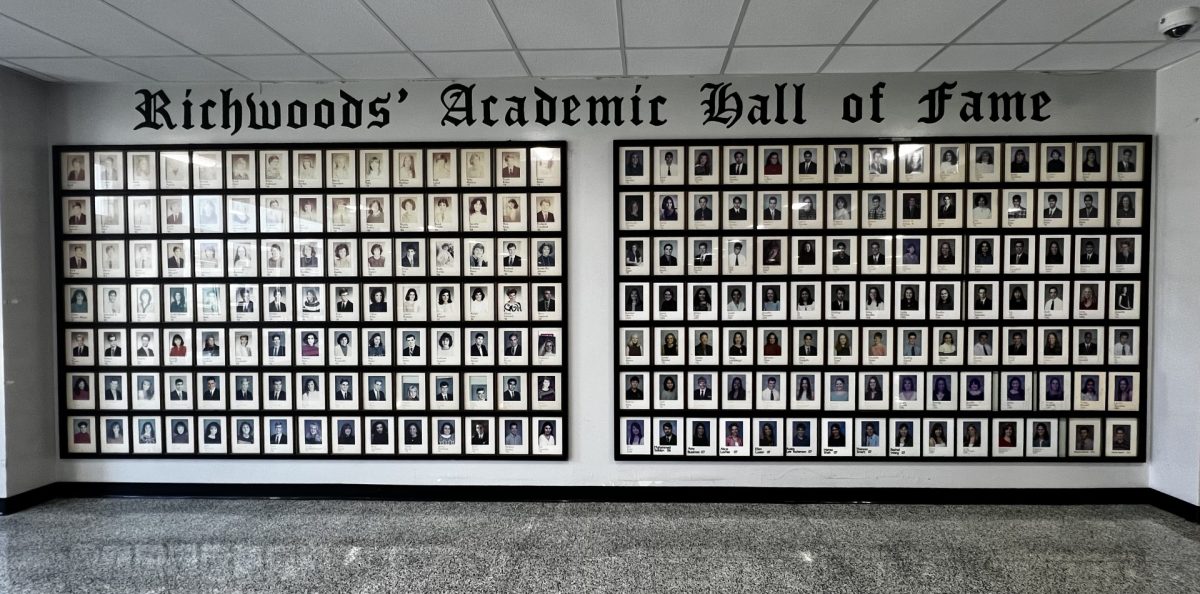

At 7:14 p.m., I know it is time for me to wrap up the interview. Dr. Baman also prepares to leave so we walk out together. I also learned that he has a daughter and two sons. On my way home, I started looking into all the possible jobs in the medical field. To my surprise, I find that there is indeed a shortage of healthcare workers in the U.S. However, I am most amazed with Dr. Baman’s project on reusing and sending pacemakers to countries where patients cannot afford such costly medical devices. Normally, the idea of reuse is promoted to conserve energy and cost as well as to protect the environment. This is the first time I come across the idea of reuse as a life-saving means. Dr. Baman is another Richwoods alumnus who has made an impact through his work. It is amazing to see what our Richwoods alumni have accomplished with their lives, whether it be serving people or creating a project to assist others.